Approach

A lot of time, thinking and effort was put into designing an implementation strategy for BYC. It was informed by many discussions, as explained in our article about the BYC model. It followed best practices as much as possible – see for example Childhood Development Initiative implementation guide.

It is also important to note that the BYC project did not fall into any of the mis-implementation traps listed by Evans and Gregory (2020):

- It was not narrow, only focusing on Young People’s behaviours, but holistic, involving every member of the BYC community. It is impossible to ignore that restorative approaches are at the core of how we do things in BYC. It is displayed in the building, visible in the rooms the young people use, regularly mentioned in staff meetings and conversations, it is part of what youth workers report to their managers, and every aspect and activity of BYC work has a restorative connection.

- It was well-resourced: funding to refurbish the building, a full-time coordinator role for two years, an advisory board (a sub-committee from the board), a support contractor to gather data and additional resources when necessary.

- It was very far from a “train and hope” model. Support was and still is available to the staff regarding training, community of practices, follow up and modelling.

James Bowes was appointed as RP coordinator and tasked with the mission of implementing the RP Strategy. The context mostly dictated James’ approach: he started in the position in Spring 2021 when Covid restrictions were in place. The Youth Club was operating very differently from what it used to. There was no group work; young people met with youth workers in pods of 2 or 4. Above all, the situation was uncertain, and it wasn’t easy to plan. James chose an organic approach, adapting to the context, the slow lifting of restrictions, and people’s needs.

James in front of BYC

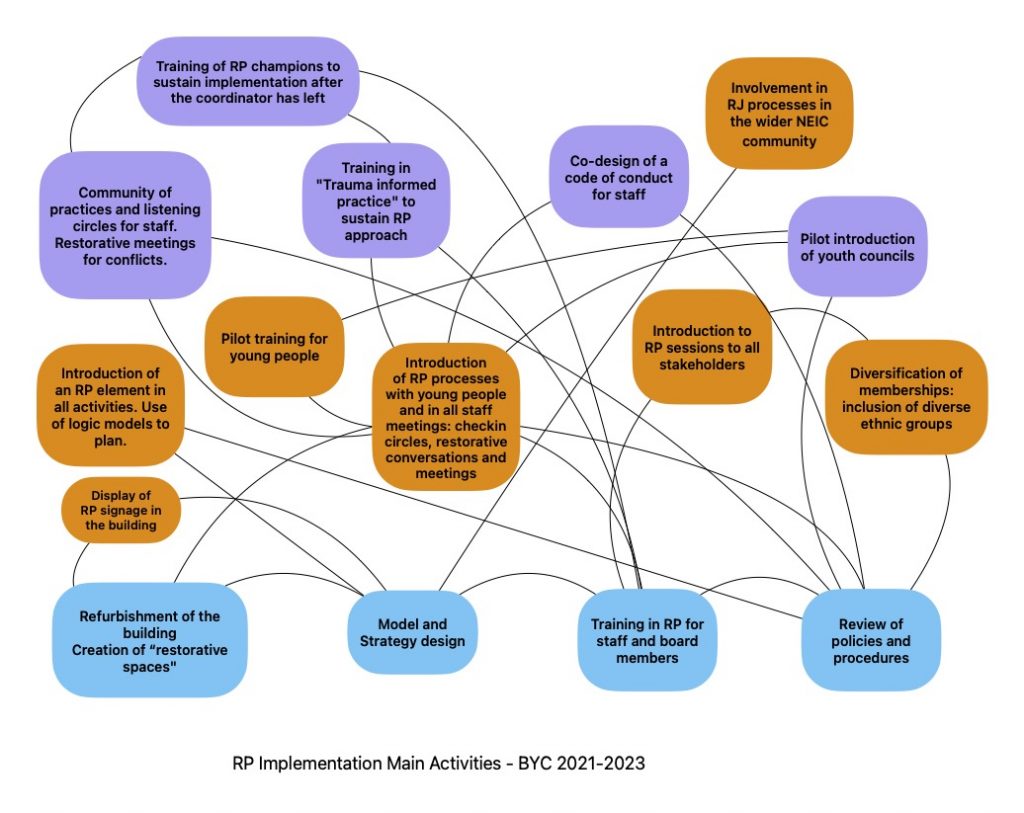

While, in some ways, progressive steps can be highlighted, it’s important to note that several processes and activities were happening at the same time. In that sense, a rhizomatic view of the process is probably more helpful, with horizontal, complex and sometimes messy growth from identified nodes: each activity tends to fuel another one, sometimes with retro-action.

Implementation nodes

This figure highlights the main activities in the implementation processes. The colour indicates a rough time frame (initial processes in blue, latest activities in purple). Each activity will be detailed in upcoming articles.

A snapshot report commissioned in March 2023 assessed the outcomes and gave some recommendations (read the report here).

These two first years (phase 1) focused on implementing RP inside the organisation before moving to a second phase to spread a restorative mindset into the wider community.

Main Learnings

The implementation process could be thoroughly and adequately researched, but for this blog, we would like to share the main learnings that emerged two years into the process.

- Coordinator position.

All acknowledge that having a dedicated staff member to lead and support the implementation is an asset. James’ energy, enthusiasm and commitment set the tone meaningfully. He completed a significant amount of work that would have been difficult to share among others: training for all, introducing RP to newcomers, modelling processes with young people and staff, liaising with stakeholders, gathering data and assessing needs and reviewing policies and procedures.

However, it is also acknowledged by staff and the coordinator himself that introducing a new staff member and a new line of management is not ideal. It led to the perception that the implementation was “top-down” and that RP was imposed as a new compulsory way of working – which in some ways clashes with the voluntary element of the restorative approach. It also blurred the management lines, sometimes creating unnecessary conflicts regarding each manager’s role and responsibilities. An external consultant position might have been better. Considering James ‘ temporary role, it would have also allowed the current staff to take more ownership of the process. It would have also allowed better management of his time: maybe a part-time position for three or four years rather than a full-time position for two years would have been more helpful. It would have allowed slower monitoring and time for skills to flourish and grow before introducing more training or addressing issues. At the end of his contract, there are concerns regarding the gap to fill in a very short time: how to share his workload? Who is going to take ownership and keep monitoring the implementation process? Are staff skilled enough yet?

- Buy in

At the end of James’contract, part of the staff and managers recognised that roughly fifty per cent of the staff was buying into the RP mindset. It is an achievement. The implementation process can take up to 5 years and is always a work in progress. However, it is also acknowledged that there would have been ways to improve buy-in. First, as mentioned above, some perceived the implementation as a top-down process: more consultation with staff during the design phase would have helped. This would also have led to an agreed and consensual definition of Restorative Practice. Secondly, as highlighted before, having a dedicated staff tasked to implement RP full-time allows some staff not to take ownership of their role in the implementation process. The coordinator was there to run restorative processes when necessary, and he spent a lot of his time being asked to solve conflicts and problems that could have been solved by staff members themselves to more efficiently support skills development in the team.

- Training

James used CDI’s RP training approach, and we will document the approach in an upcoming article. Most staff members have enjoyed it and found it helpful. However, it does not mean it was easy to implement. James recognised at some stage that staff needed more support than just a community of practices and listening circles, and he suggested that all undergo specific training on Trauma-Informed practice. It seems to have been a significant step: even when practitioners are willing to engage in restorative processes and approaches, they face the challenge of triggered participants and must deal with their own emotional triggers. The training equipped staff members to better deal with the emotional regulation necessary to engage in RP. We would recommend similar training to any other youth organisation, especially when working with young people who have experienced a lot of traumatic events – the Pandemic itself exacerbated or created new traumatic experiences.

- Monitoring and evaluation

There is growing attention to monitoring and evaluation in youth work and community development, and this was given much attention in the design process and strategic planning: logic models, clear outputs and outcomes, and clear strands of work. However, keeping track of what is happening in the day-to-day running of a busy organisation such as BYC takes time and effort. This type of youth work is also much more informal than schooling or youth justice work, where outcomes are easier to measure. First, a “strand report” was introduced so people could report any activity, its restorative element and its outcomes in line with the Strategic Plan Strands of work. Although an effort was put into filling them, with dedicated time allocated to staff, it was still difficult to gather enough information. At the same time, there was not enough clarity about what the data was collected for and what indicators they would give. This is still a work in progress: the strand forms were simplified first with no better result. A specific question on restorative approaches has been added to the monthly report each youth worker has to complete. A form for significant restorative processes is currently piloted. We will come back to this in an upcoming article.

a busy day in BYC

Next steps

The following steps have been highlighted in the snapshot implementation report made in March 2023. They are being actioned currently, and we will be able to tell more about this in a few months.

- Keep offering training according to needs, Community of Practices, and build capacity by training ‘Champions’ and ‘Trainers.’

- Agree on or clarify or implement more transparent processes for decision-making, conflicts among Staff, and grievances, and explore redefining management/leadership roles.

- Agree on, clarify and implement more explicit standards and processes for young people’s training and participation (including but not limited to the Youth Councils).

- Design a more specific plan for the second phase of the implementation in the wider community, starting with Parents’ involvement and mapping more specific objectives and outcomes when it comes to engaging with the various stakeholders and partner organisations in the area.